KEY CONSIDERATIONS

Designing a Retort System for Shelf-Stable Food Packaged in Flexible and Semi-Rigid Containers

From filling to sterilizing, flexible packaging must be handled differently than rigid containers.

By Chris Barbier

Consumers today increasingly prefer flexible and semi-rigid packaging as compared to rigid materials in a growing number of human and pet food products. Consumers perceive pouches, bowls and trays as new and innovative, space saving, convenient and more sustainable through less waste. New microwaveable packaging is a big part of the convenience factor. Not only do flexible and semi-rigid materials help to boost sales, but this packaging also lowers unit cost and can reduce sterilization time by up to 50%.

Making the switch from rigid containers such as steel cans and glass jars and bottles is not as simple as substituting one material for another. Flexible and semi-rigid packaging does not fill, seal, handle or perform in a retort like cans or jars. Basically, a new line is required.

ADVERTISEMENT

Major Equipment Components

In addition to conveyors and accumulation lines, there are five major equipment categories that comprise a retort pouch, bowl, and tray line for human and pet food.

- Filler/Sealer

- Retort Automation System — including self-stacking trays, tray loader and unloader and tray stacker and de-stacker

- Overpressure Retorts

- Retort Delivery System

- End of Line Packaging Equipment — including dryers, labelers and coders, case packers, case palletizers, stretch wrappers, etc.

In designing a packaging line for pouches, trays and bowls, the desired line speed drives the majority of the design decisions. For example, the line speed dictates the type and sometimes the brand of filler/sealer. The filler/sealer has a characteristic output format for the filled and sealed packaging such as single file or two-up. There may possibly be more than one filler/sealer on the line. This output stream impacts every machine and handling decision that follows.

A major piece of equipment immediately downstream from the filler/sealer is the retort material handling system, specifically the tray loader and stacking equipment. The tray loader collates the packages in a pattern conducive to the tray design, which is quite different from the retort baskets used for cans and jars. Rather than layers of rigid packaging separated by slip sheets in a basket, flexible packaging is arranged in a series of rows one layer deep in a shallow tray. Trays are then stacked on top of each other and formed into cubes, and the cubes are moved into and out of the retorts.

As a rule of thumb, gantry-type tray loading and unloading systems are cost effective for line speeds greater than 500 containers per minute (CPM). Many pouch, semi-rigid tray and bowl line speeds are below 500 CPM. At these lower speeds, robotic loading makes sense in terms of capabilities and capital cost. Robots can also give the food manufacturer greater line flexibility for handling packages of different dimensions and configurations.

Example of flexible and semi-rigid packaging for shelf-stable applications.

Photo courtesy of Allpax

Tray Design

Once the line speed and filler/sealer decisions have been made, tray design becomes critical. The layout or pattern of packages in the tray is most efficient — highest output — when the number of rows in the tray is a whole-number multiple of the number of infeed lines. For example, if there are four infeed lines, the optimal tray design would be 4, 8, 12 or 16 rows wide.

The tray, while simple looking, must be well engineered in terms of promoting optimum energy flow around the package. The tray must be rigid enough for stacking and de-stacking as well as to withstand the harsh environment within a retort. It must also be free of burrs or defects that may damage the integrity of the flexible package.

Trays can be fabricated from stainless steel, aluminum or injection-molded plastic. Metal and plastic trays each have advantages and disadvantages in terms of upfront cost, unit cost and service life. Injection molded plastic trays require a hefty upfront tooling charge. The unit cost, however, of injection-molded plastic trays can be as much as one-tenth that of stainless-steel trays. Plastic trays are not a good option when the size exceeds 40-in. x 40-in. due to issues related to strength and rigidity. Plastic trays typically have a service life of about two years. Metal trays have a high unit cost but can deliver extended service life well beyond that of plastic trays.

Once the conceptual tray/cube design has been fixed and the tray cubes are dimensioned, then retort sizing begins. It is sometimes necessary to revisit the package size at this point, since a small change in the dimensions of the package can sometimes greatly enhance the efficiency of the line design.

Retort/Cube Capacity

The density of flexible containers compared to rigid containers is about one-third less in a fully loaded retort when comparing equivalent numbers of baskets and cubes. For example, the fully loaded retort of 3-oz cans compared to 3-oz pouches in an 1800-mm-diameter 6-basket/cube retort is 61,560 cans versus 22,032 pouches. Flexible containers typically sterilize faster than rigid containers though, and that has to be considered when designing the retort room. Lower cycle time also means more frequent loading/unloading cycles. Total retort loading and unloading and processing time must be estimated due to the throughput expectations of the line. Increasing the number of retorts or ordering higher capacity retorts may be required to meet output production needs of flexible or semi-rigid containers.

Robotic tray handling system

Photo courtesy of Allpax

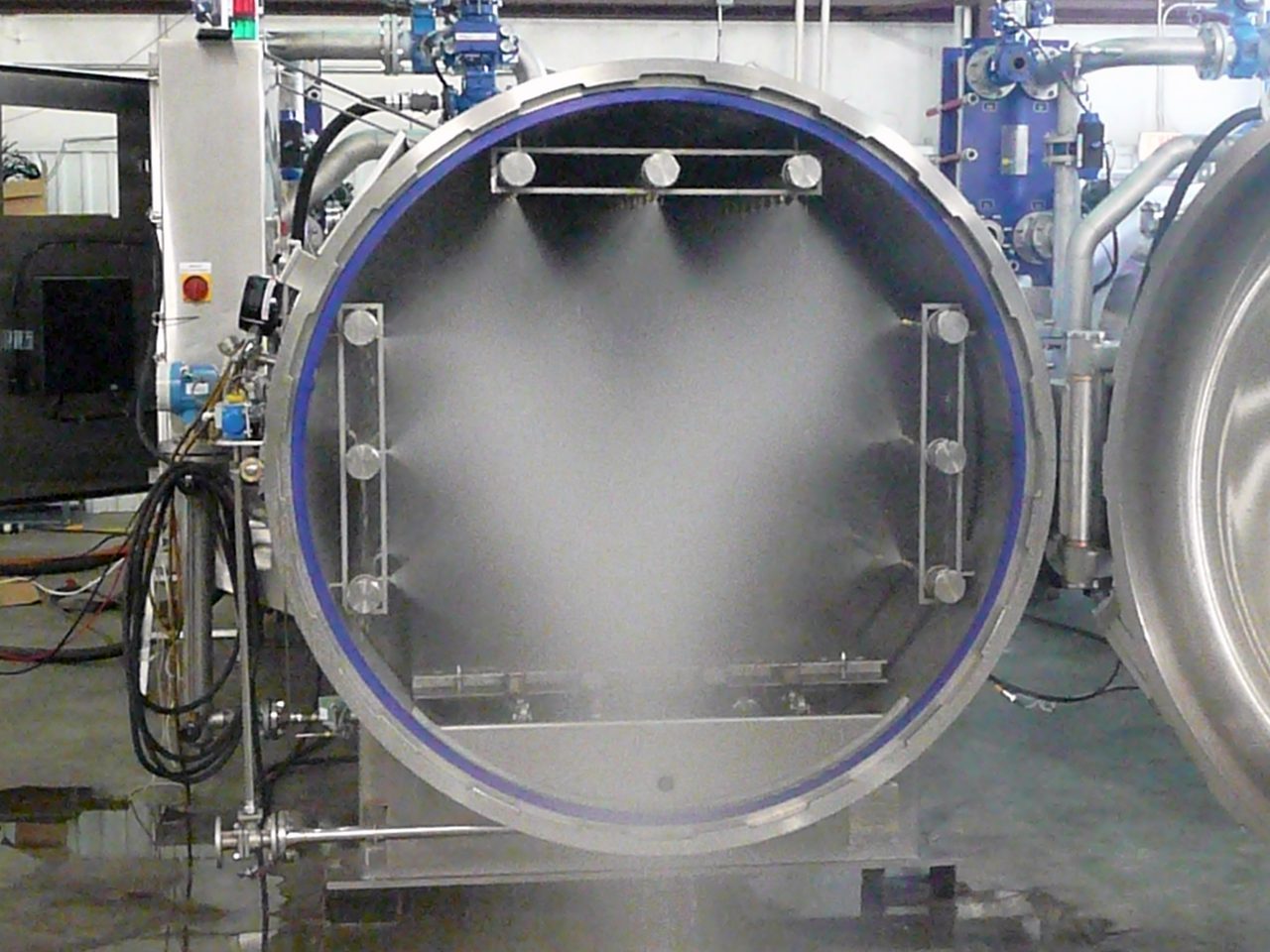

The Retort Process — Overpressure Retorts

Sterilization of human or pet food packaged in a pouch, bowl or tray must be accomplished with an overpressure retort — a retort that adds pressure during the come-up and sterilization process steps. Without added overpressure, which compresses the package, the heat and resulting pressure build-up inside a flexible or semi-rigid package would cause the package to expand and potentially rupture.

Different overpressure type retorts include:

- Water Spray — static, horizontal reciprocating agitation, or rotary end-over-end-type agitation

- Rotary Water Immersion

- Steam-Air — static or rotary

Each of these different types of retorts can have its own quality and processing speed effect on the shelf-stable food being sterilized. Utilizing a multi-mode laboratory retort during product development is one of the most effective means of understanding which type of retort and processing parameters will enhance the unique qualitative properties at the production rate desired. The advantage of a multi-mode retort is that all the various sterilization options can be tested, and the optimum process type determined. Multi-mode lab retorts are available at many commercial food labs and can also be leased or bought for in-house use. One of the tests that must be performed is a pressure profile of the package. This test measures the deflection of the package under processing temperature and pressure conditions and is used to identify the proper overpressure profile during come-up, sterilization and cooling to ensure package integrity.

If the control system on the multi-mode retort is the same as on the production retort, scale up from test to production can be seamless. Automated control systems on tier one production retorts typically support FDA requirements for electronic record keeping. The retorts human machine interface (HMI) should enable fast changeover between products and provide maintenance personnel with the type of on-machine information required to keep these complex sterilization vessels running at optimum capacity for many years. Remote diagnostics that conform to a user’s security protocols is vital for fast, effective troubleshooting and maximum uptime. Manual control costs less upfront but is outdated as it raises the risk of operator error and makes record keeping a burden.

Water spray retort

Photo courtesy of Allpax

Retort Delivery — Retort Loading and Unloading

A fully automated retort room, including material handling from start to finish, is the sensible system to invest in to achieve the lowest labor costs, highest worker safety and reduced risk of recall. Typically, a fully automated retort room requires one to two operators per shift as opposed to four or more operators per shift for manual operations. Fully automated systems also reduce human density on the plant floor, a critical consideration today when the threat of security issues, human error, and airborne contagious disease is ever-present, and plant managers are looking for ways of ensuring uninterruptable production.

Other Critical Considerations

Investigate energy and water savings systems in a new installation for lower cost of operation and greater operational sustainability. Stainless-steel stress corrosion cracking, a condition that severely reduces a retort’s service life, can be avoided through plant monitoring of water chemistry and the inclusion of water treatment systems. The plant can also invest in a higher-grade stainless steel that provides resistance to stress corrosion cracking. Discuss with the supplier the cost effectiveness of purchasing a dual-mode retort. Dual-mode retorts, as the name implies, can be changed over from handling rigid containers to flexible containers, offering the organization greater ability to adapt to changing market conditions.

For a new flexible or semi-rigid processing and packaging line, find a retort manufacturer that can provide either a complete line solution, from the kitchen all the way through to final packaging, or one that will build and integrate an automated retort room with retorts, automation equipment, retort delivery equipment, integrated and validatable control system and ancillaries. These suppliers can offer full-line factory acceptance tests (FATs) prior to shipment. A full-line FAT integrates all the elements of the system and confirms that the line is operating as specified, thus reducing startup time and overall project costs. From an integration and overall equipment efficiency standpoint, a full-line FAT offers the optimum solution for a new line.

Chris Barbier is an applications sales engineer for Allpax with more than 15 years of experience in thermal processing and in-container sterilization of low acid foods in hermetically sealed containers. He assists new and existing customers with determining retort and material handling requirements for all packaging types.

Lead image by sergeyryzhov / iStock via Getty Images Plus

February 2022 // flexpackmag.com